Breathing : Part 1 of our “Skills You Might Suck At” Series

Breathing. You’ve done it literally since the moment you were born. Every minute, every day, every year of your life.

So no problem right?

You could breathe in your sleep. In fact you do it all the time.

But to be honest? I see a lot of people who really suck at breathing. And if there’s one thing you should be good at, it’s probably the thing you’ll do until you die. So at the risk of being overly simplistic, I’m starting the ‘Skills You Don’t Have’ Series with your breath.

Breathing is important because you do this ALL the time, and also because breathing mechanics are important in how the rest of your body works. That includes how you move and whether you have pain. For example, breathing affects your transverse abdominal muscles, which stabilize your low back and support your upper body movements. Breathing regulates your body’s pH (oxygen in and carbon dioxide out). It affects your general mental state like how stressed the heck out you are (ever take a deep breath when you’re stressed out?). It can affect your digestion, since it will change the pressures on your digestive system. But wait there’s more! Breathing can affect your nervous system, your immune system…all sorts of good things (Kox 2014).

So how do you breathe?

Breathing starts with the diaphragm, which is a muscle that stretches across the bottom of your rib cage. The diaphragm contracts and flattens out, creating more room in your rib cage (which is where the lungs live). Air comes down the nose and mouth, into the throat, and then into the lungs since the air pressure inside your rib cage drops when the space inside gets bigger. When you exhale, air gets pushed out because your diaphragm relaxes and the elasticity of your rib cage and diaphragm compresses the air inside and squishes it back out into the air around you.

So where do things go wrong?

Take a deep breath. (Yep, right now.) Most people tip their head back, bring their shoulders up, and tilt their chest toward the ceiling. That’s not great. It means you’re lifting your rib cage with your accessory muscles instead of using your diaphragm. The muscles along the top of your rib cage are known as the “accessory breathing muscles”—”accessory” muscles meaning you don’t need them all the time, just when you really need to get lots of extra air in. Which you shouldn’t need in situations like sitting on your bum in that chair. Your diaphragm is what really helps create space.

What should happen is:

- Diaphragm comes down

- Belly and lower rib cage expand outward

- Chest doesn’t do much

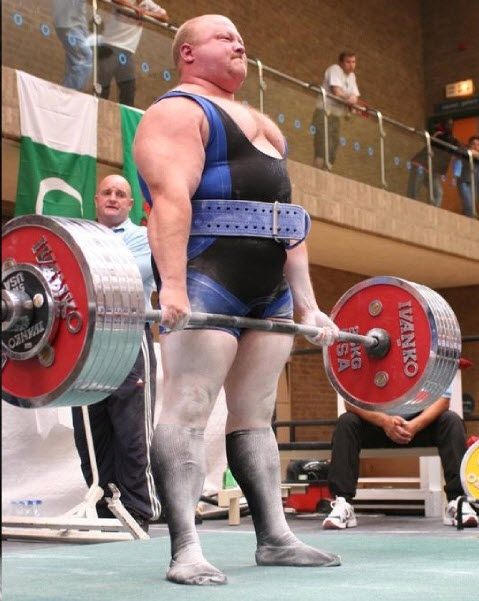

After that you exhale, which is just your diaphragm relaxing, increasing pressure on your lungs, and pushing air out. Now if you sprint as fast as you can, your body needs more oxygen, you breathe deeper and you start using your accessory muscles. If, instead, you’re doing something like lifting or sitting, breathing from your diaphragm is going to support your body better. Your diaphragm pushing down increases ‘intraabdominal pressure’—the pressure in your belly area that pushes out against your abdominal muscles and helps stabilize your low back. It’s like a balloon sitting between your pelvis and rib cage. Olympic lifters are really great examples of this, because you can see the intra-abdominal pressure not only stabilizing their spine against all the weight, but also providing a solid anchor for the muscles in their upper body that are contracting to lift the weight.

Am I doing it right?

So not too complicated of a concept, but breathing correctly sometimes takes awhile to get the hang of.

Need an example? Watch how a baby breathes. Or if you (like me) don’t have a baby conveniently on hand, use these cues:

- Stick a hand on your chest and one on your belly. Keep breathing or take a deep breath and watch your hands move. With inhaling, the hands may both move out or one may move out more than the other. What you shouldn’t see is the lower hand moving closer to your spine as you inhale. Yes you can suck your belly in to move your hand closer to your spine, but that’s not how you get air in your lungs, just how you suck in your gut (picture time!). When inhaling normally, the bottom hand should move out and the top hand really shouldn’t move much at all. On exhaling, same thing—bottom hand moves back in toward your body and top hand doesn’t do much. If you breathe deeply (like sighing), both top and bottom hands move some, though the bottom hand should move more. What I notice is that with a lot of people just the top hand moves when sighing (not good).

- If you want to further check your breath skills, stick your hands on your waist like you’re angry at somebody. As you breathe, you should feel your abdominal muscles expand under not just your fingers but your thumbs too. You’re not actively pushing out with your abdominal muscles with normal breathing (not like when you’re trying to go to the bathroom). The muscles naturally expand out all around your abdomen as your diaphragm pushes down. It’s not your belly pushing out like you’re pregnant, it’s a whole-abdomen expansion—front, sides and even along the back. The same goes for your rib cage. The bottom of your rib cage will expand slightly the whole way around as your breathe. Your can move your hands north from your hips to the bottom of your rib cage to see if that’s the case.

- There’s also props like belts you can use as cues to see how well you’re breathing. These can be helpful in the learning phase, since they offer resistance in the places there should be movement.

- It’s important to make sure you’re breathing right not just laying around but also as you sit, stand, walk, lift, et cetera. If you’re really confused by this, start by laying on your back and lift your feet up on a chair since this relaxes tension on the core. That’s easiest, but then push yourself to see if you do this throughout the day in your normal motions.

- Making sure you’re not hunched over while you sit is key in being able to breathe well while seated. If you slouch, your diaphragm doesn’t have anywhere to go and you have to use your chest to breathe. On top of that, creating a small amount of intra-abdominal pressure while you breathe helps you sit up without having to force your muscles into good posture. Let’s be honest–willpower is not the most effective tool for changing posture long term. Breathing more fully makes sitting infinitely easier. See our sitting article for more details on sitting.

So those are the breathing basics.

Your ability to breathe will also change with posture, how often you move, restricted motion along your spine, or even fascial (muscle, ligament, soft tissue) adhesion. People always say ‘everything is connected’ in the body, but it’s hard to see how that applies when it’s your own body. Examples I see regularly are crappy breathing patterns contributing to shoulder issues, lack of spinal flexibility preventing the ability to take a deep breath, or fascial restrictions in the leg or back or shoulder creating tension as you breathe. In those cases, it’s beneficial to have a trained movement professional to identify movement deficits that need correcting. For most people though, working on your breathing mechanics at home (and at work and in the car) is a great first step for improving movement, body function and reducing long-term pain. So just keep breathing…but make sure you’re breathing well.

If you want to take a deeper dive into breathing, check out one of the following:

- Our Breathing Video on YouTube

- Diastasis Recti by Katy Bowman (Can be Purchased Here). Diastasis Recti is actually a specific condition, but it has its roots in improper pressures in the abdomen, so she does a great job talking through breathing and what your core is actually supposed to be doing.

- Yoga: If you’re looking for some in-person practice and guidance, yoga classes are fairly widespread and consistently incorporate beginner breath work and progress it by pairing breath with movement. In addition to getting you moving more, this can be helpful in integrating good breath patterns into whole-body movement. (One note of warning: sometimes exercise instructors will say to suck your belly button to your spine to activate your core. In some bodies, activating your core can move the belly button inward, but if you’re sucking in your gut like you would in a picture, that’s not the way you want to be activating your core in movement or daily living.)

- Wim Hof (the Iceman). He doesn’t spend a whole lot of time on breathing mechanics, but he does have very accessible breathing exercises. His work uses breath to affect the nervous system, immune system, and general well-being. He’s a unique guy, but it’s interesting work. Check it out if you’re wanting to use breath as a tool beyond just having better mechanics.

- Many types of meditation and mindfulness use breathing as a tool to achieve relaxation. If breath-work seems most appealing because it helps control stress, consider working on a beginner level of mindfulness. My favorite is the Headspace app, but there are plenty of great options out there.

The next topic in the ‘Skills You Might Suck at’ Series is Sitting so get some breath work in, then head that way!

Kox, M., van Eijk, L. T., Zwaag, J., van den Wildenberg, J., Sweep, F. C., van der Hoeven, J. G., & Pickkers, P. (2014). Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(20), 7379-7384.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.