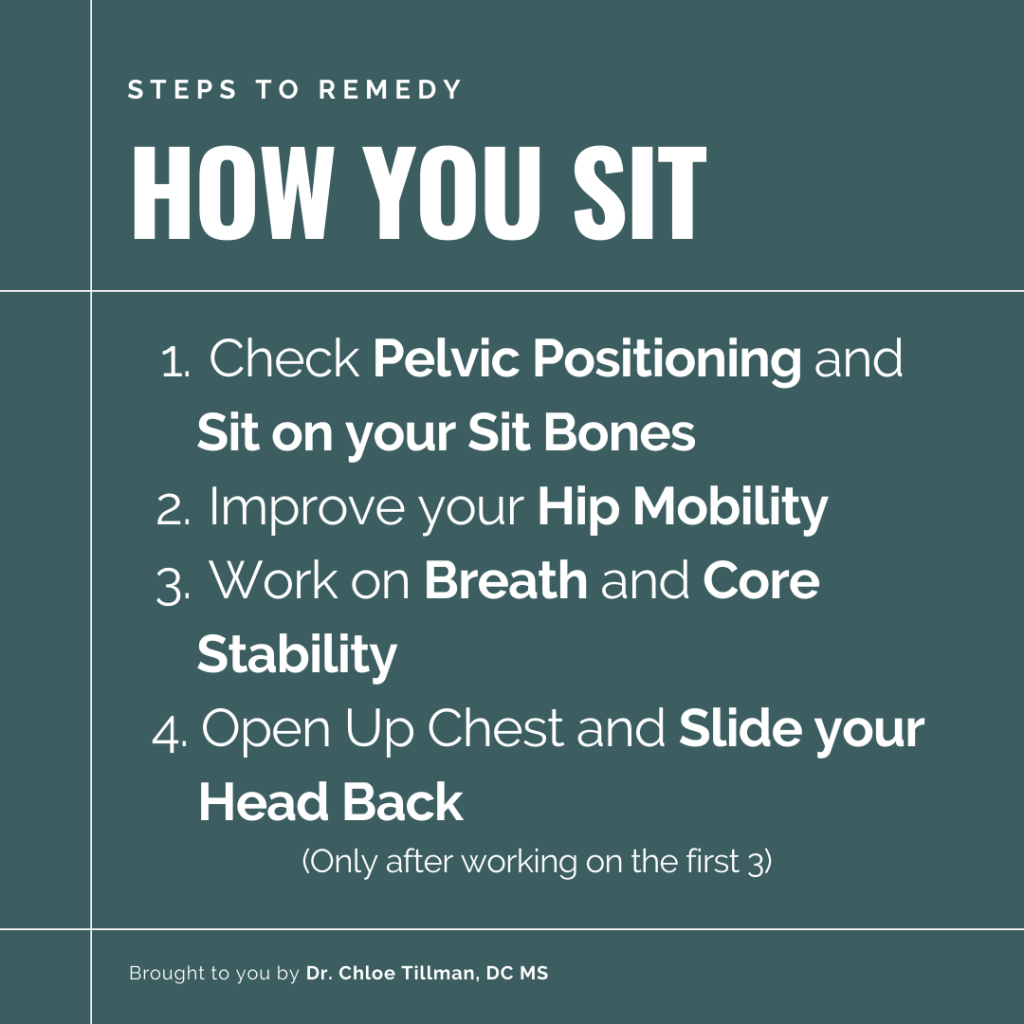

Standing is Skill #3 in our series Skills You Might Suck at. If you haven’t already, go back and check out Parts 1 (Breathing), 2, and 2.5 (Sitting).

Standing has a way of making us realize that we feel older than we should. Breathing? We don’t usually even realize we suck at until someone points it out. Sitting? We feel ok sitting unless we sit for long periods of time, but standing? Standing gets tricky. Plenty of people–younger folks included–notice pain, discomfort or weakness when they’re standing around. This is especially true switching to a standing desk or a job where you’re on your feet more. Some notice the pain while standing, some are sore later on in the day, and some do the back-and-forth sway to keep discomfort at bay.

BUT if your biomechanics (the ways you move your body) are good, there shouldn’t be pain with standing. What’s more, the way that some of us stand puts pressure in places there shouldn’t be pressure. Which means we’re increasing the likelihood of degeneration and pain in the future, even if we don’t notice pain right now.

So how do you know whether you suck at standing?

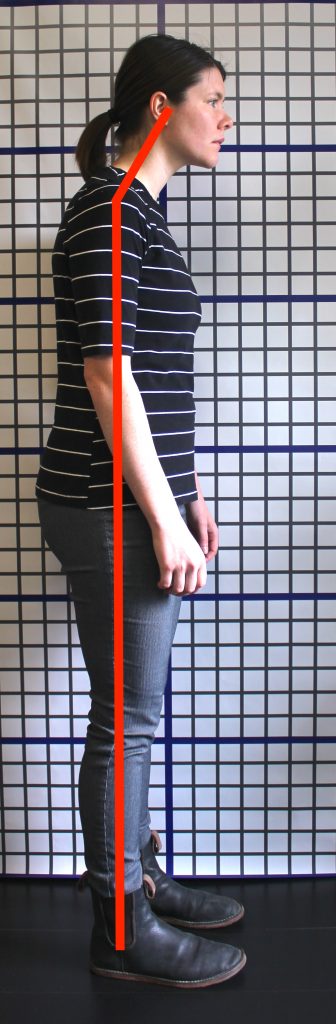

For one, if you’re having pain while you’re standing, you’ve got an issue. But generally that pain comes from tissue damage and joint issues that arise from putting pressure where it shouldn’t be. And while fixing standing problems is more complex than fixing sitting issues, you can still make improvements just by assessing how you stand now. To see how you stack up, check yourself against these cues. (Or have a family member check you from the side or take a picture for you to see.)

From the Front:

Your feet should be forward (meaning the outside of your ankle and your foot should line up) your knees straight, and your hips and shoulders should line up evenly on the horizontal plane.

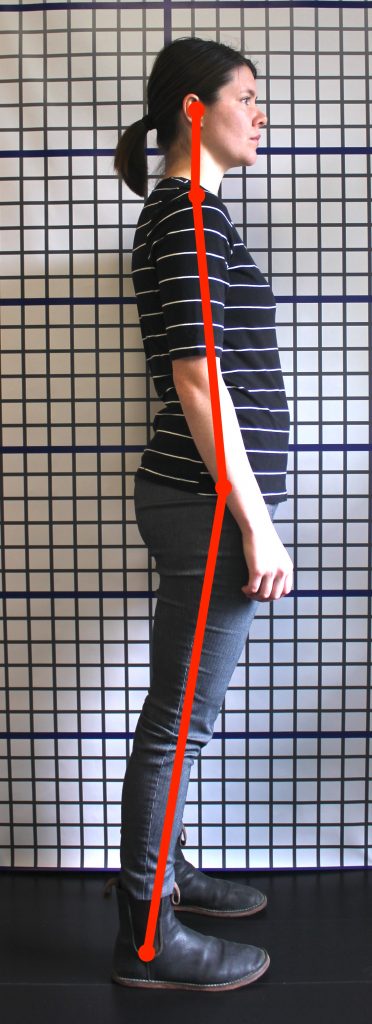

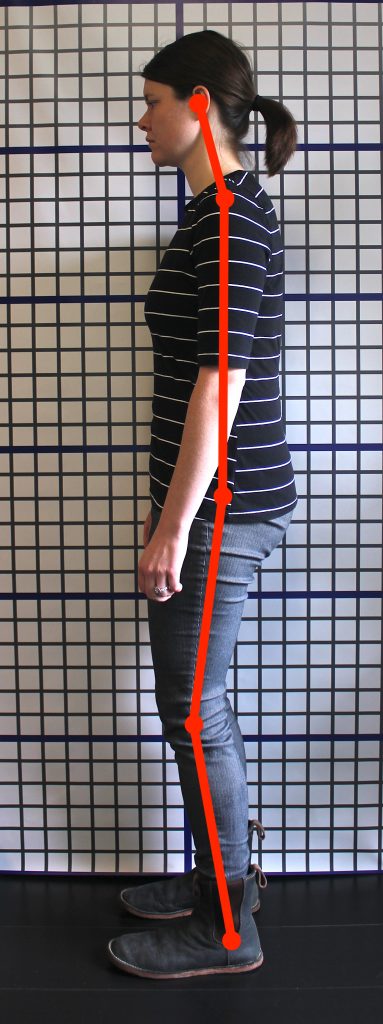

From the Side:

Your ankle bump (lateral malleolus) should line up with the middle bump of your hip (greater trochanter), the top of your shoulder (AC joint) and your ear hole (external auditory meatus). The front bump on your pelvis (ASIS) should line up horizontally with the back bump on your pelvis (PSIS) and should stack vertically with your pubic symphysis (i.e. the pubic bone, the bone that sits just under where your bladder is).

Note: The stripes on the shirt fall funny to where the rib cage looks a bit flared. Our mistake! Should’ve been straightened before the pictures. Also the right hand had to cover the greater trochanter or the pubic symphysis, so the latter is covered.

Common Problem Patterns to Spot are:

- Hips are way in front of your ankle so you stand like a jelly bean

- Hips lined up with your ankles, but your knees don’t fully straighten

- Knee caps are clenched (your quads actually, but they lift your knee caps)

- Too much lumbar arch.

- Excessive thoracic forward curve.

- Too little cervical curve.

- Your knees collapse in toward each other.

When we talked sitting, most issues could be remedied using the cues we talked about and a little strategic mobility work (with help from a practitioner). Poor standing patterns take more work to fix. They tell you a lot more about the dysfunction you’ve accrued over time. We see the impact of our lifestyles in weak feet, tight calves, sleepy glutes, tight hip flexors (psoas) and hamstrings, an unimpressive core, thoracic stiffness and turtle-y heads. These factors are all heavily impacted by our lifestyles, especially by sitting. But where do we start fixing our standing issues?

Standing Factor #1: Your Heels. (The ones on your shoes, not the ones attached to the bottom of your feet)

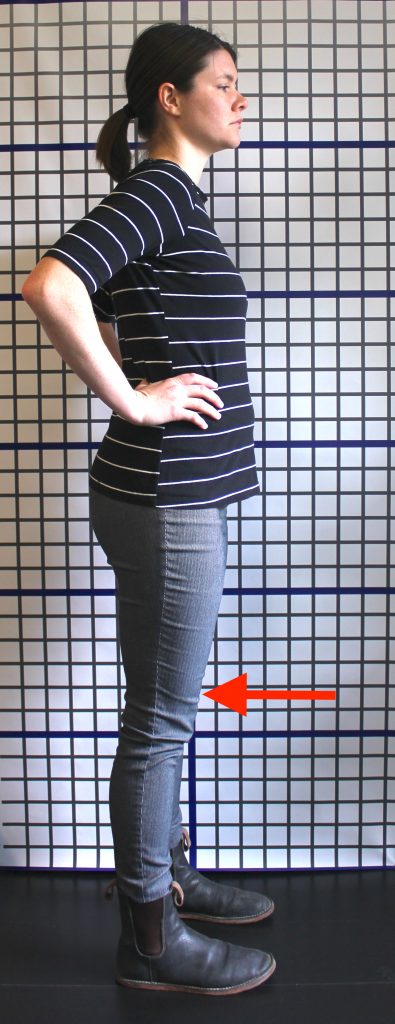

We’ve mentioned that in sitting, your sit bones (ischial tuberosities) are your base of support. When it comes to standing, your feet are your base of support. Most people wear shoes that have a drop between the heels and the toes. These shoes push their center of gravity over the front of their feet, which puts more pressure on the smaller, less-able-to-weight-bear structures at the end of their feet. Over time that results in issues like bunions, tight calves and stiff ankles. It also alters tensions throughout the legs because if your legs and ankles are in one position over and over again, your tissues create tension to hold you there. After holding tension over long time, your muscles physically alter in length, which means you lose your range of motion. The more we sit, the less able we are to bring our toes toward our head.

The effects of this tension don’t just stop at your ankles and calves though. Tight calves also make it harder to straighten your knees all the way. Which means more pressure on your knees. And more wear and tear over time on your knees. And eventually means more pain. I guess technically knees are replaceable, but I’m hoping to keep my OG pair or knees.

Additionally, because your weight is over your toes more, your center of gravity shifts forward. Your calves adapt for some of that shift, but rather than fall face first, your lumbar tends to arch more and you rely more on back muscles than on your core. Over time the changes in pressure on the spine and muscles lead to joint stiffening and degeneration. It’s easy to think the aches and arthritis are due to age, but that’s an easy cop out. Just like my car has more wear and tear if my wheels aren’t aligned, my body gets more wear and tear if the parts aren’t aligned.

Note that I’m not just talking about high heels here—dress shoes, tennis shoes, boots—lots of shoes have that heel. To change the effect that heels have on our structure, I recommend starting working with ankle and calf mobility. The ideal solution is that they eventually switch into zero-drop, flexible shoes that don’t shorten their calves. That said, a jump in type of shoe–if made too quickly–can result in injury. Check out the shoe article on our website and the resources listed in it if you’re looking to transition. Folks on a concrete surface can still use a little cushion, but go for a shoe that does that while still offering less drop and some flexibility.

Standing Factor #2: All the muscles that attach to your bum. And your pelvis.

Note: Some of the patterns we frequently see (like an excessive lumbar arch) are aggravated by a positive heel on your shoe. That’s why we started with your heels, because issues with the foundation can affect the whole structure. It’s a waste of time to patch drywall cracks until you’ve fixed the foundation of your house.

Beyond that, when we look at the body from the side, most of the issues with lower body deviation forward or backward either come from the ankle or the hip. Here are a few common variations of “You suck at standing because…”:

- Your knees are bent: If the knees can’t fully straighten, this typically results from really tight hamstrings and a lack of hip mobility. The lumbar is usually flatter, and these people tend to sit a whole lot (and are more commonly male, whereas females tend towards more lumbar curve).

- Solution: There’s a decent chance you should be moving a lot more! Also hip and pelvis mobility work along with specific hip exercises to help your hips reach full extension. This doesn’t include the bend over and touch your toes hamstring stretch, but should (eventually) include the progression toward being able to get on the floor (because these folks usually can’t)

- Your knees are locked out: When the quads are always clenched and the knee caps lifted, typically your weight is forward and you’re standing like a jelly bean with your pelvis tilted forward or you’re compensating for your heels. The pelvis is usually tilted forward, and this is more frequent in females.

- Solution: Heavy hitters are foot strengthening, shifting your weight backward (check your shoes!), and breath work to allow the abdomen to relax a bit. From there, correction varies per person.

- Your back is arched: AKA excessive lumbar curvature. As mentioned earlier, our pelvis should be in neutral with the top hip bone on the front lined up with the bump on the back or the pubic symphysis. Isolating this motion can be really tricky for people to grasp. It’s kind of like a hip thrust–but think less Michael Jackson, more Will Smith Jump On It. Maintaining this position takes a little glute and core engagement and making sure our psoas (hip flexor) isn’t too tight. Psoas tend to get overly tight when we (surprise!) sit a lot.

- Solution: It takes more than 30 seconds worth of stretching to relax that psoas and to limit the lumbar curve—it takes a little core work, a little (or a lot) of walking (endurance activity for the glutes), changing some daily sitting habits, some joint mobility work, and making sure that you’re not arching your lumbar to make up for shoes that push you forward. Changing this takes some effort–hit that resource section!

- Your knees cave in: Knees that roll in toward each other indicate either weak abductors and external rotators like gluteus medius or ankles that are caving in toward each other too.

- Solution: If it’s from the hip, Jane Fonda leg lifts are the usual recommendation but they don’t get you very far. Doing single leg standing type balance work tends to give your more bang for your buck. (This also strengthens the feet. I find that when hips are weak, feet usually are too). If it’s coming out of your feet and ankles, the traditional answer would be to get an orthotic. It takes a very, very wrecked pair of feet for me to agree with that. Before you go that route, head to our website and check out our foot articles. Work on you feet and ankles, and your knees tend to straighten as well. Katy Bowman’s Whole Body Barefoot is probably the best resource I’ve seen on this.

Standing Factor #3: Thoracic stiffness.

Your thoracic spine is that area in between your shoulder blades. Stiffness here means your head and shoulders hang too far forward. Sometimes people hide their thoracic stiffness by arching the low back more, which makes the head appear to be lined up with the lower body.

The biggest clue for thoracic stiffness is a poked-out rib cage. If you slide your hands down your rib cage, you shouldn’t really feel the end of it because it should slide right into the contour of your abdominal wall muscles. Obviously a little more or less belly in that area can make this cue less helpful. You can also try standing with your bum and back against the wall and see if your thoracic spine, elbows and hands all touch when you assume the snow angel position. If standing makes you stiff between your shoulder blades or a little lower down, this is a likely contributor.

Solution

When people are stiff through their torso, they often can’t drop their rib cage while their pelvis is in neutral. I’ve seen some patients pick it up through trial and error over and over, others have to get some help with joint or tissue mobility first, and some need one-on-one cuing with motion or breath work. Everybody is a little different. But start with getting a neutral pelvis, and eventually work yourself to where you can slide your torso front, back, and side to side and rotate it separate from your pelvis. Then work on standing with your rib cage lined up directly over the pelvis. Breathing well with your diaphragm contributes to your success here because (who knew?!) your diaphragm lives in your torso.

Don’t forget your turtle head:

Once your thoracic spine is mobile, it takes just a slight chin tuck to bring your ear over your shoulder. Just like sitting, when the bottom half is lined up, the top half is easier to put where it should be. Forward head posture is typically a result of a lot of sitting and close-up work. When you’re standing, if everything under your neck is lined up, you probably only need to slide your head back a bit to be perfect.

I put thoracic stiffness and neck positioning last because while a lot of people have their head way in front of their body (anterior head carriage), what keeps them from being able to change that over time is the shifting foundation that head sits on—the feet, knees, pelvis and core.

So on the whole:

Start at your foundation and at least work on getting your feet and ankles more mobile and lined up well. From there, start to shift your weight backwards and re-check what your alignment is from the side. Make sure ankles, knees and hips all line up, and check the tips above if they don’t. Then look at your rib cage (which changes where your shoulders sit) and then your head.

And then….check back with us to see about the next Skill You Might Suck At: Squatting!

Resources:

- Standing is harder to fix without some professional help, but start with this article and the resources below. If you’re already having pain standing, check with a movement professional to help you start making progress.

- Katy Bowman‘s Move your DNA (for the average bear) or Dynamic Aging (for the mobility-challenged bear)

- Yoga classes are a great place to start strengthening feet and hips. They come in different levels of difficulty, teaching styles, and are available in most areas. Martial arts tends to strengthen feet as well, as both of these exercises require a stable base to work from.

- Barefoot walking can help strengthen the feet, even if just around the house. I really can’t emphasize how much the strength of your feet provides a foundation for how you stand.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.